Trying to establish the historical genealogy of the concept of hegemony I was prompted to read the entry on Personal Loyalty in Emile Benveniste’s Dictionary of Indo-European Concepts and Society (Hau Books, 2016, 75-90). Part of it was predictable (and consistent with Heidegger’s analysis of Roman hegemonic domination in his Parmenides, from 1942): “fides develops into a subjective notion, no longer the concept which is inspired in somebody, but the trust which is placed in somebody.” “The one who holds the fides placed in him by a man has this man at his mercy. This is why fides becomes almost synonymous with dicio and potestas. In their primitive form these relations involve a certain reciprocity: placing one’s fides in somebody secured in return his guarantee and his support. But this very fact underlines the inequality of the conditions. It is authority which is exercised at the same time as protection for somebody who submits to it, an exchange for, and to the extent of, submission” (88). Calls for a hegemonic understanding of the political have that irreducible character of unequal exchange—trust for submission, constraint and obedience. This is clearly visible, by the way, in the early Antonio Gramsci, whom we are reading right now in a working group. Persuasion—by the party which holds the secret of history—is obedience. Those who have faith in the party must first of all obey. “Fides in Latin is the abstract noun corresponding to a different verb: credo,” “in these terms we are back once again with notions in which there is no distinction between law and religion: the whole of ancient law is only a special domain regulated by practices and rules which are still pervaded by mysticism” (90). This is presumably why Gramsci may claim that “most people do not exist outside some organization, whether it calls itself the Church or the Party, and morality does not exist without some specific, spontaneous organ within which it is realized. The bourgeoisie is a moment of chaos not simply where production is concerned, but where the spirit is concerned” (Pre-Prison Writings, Cambridge UP, 1994, 72).

But something else in Benveniste’s entry intrigued me. It is the reference to Tacitus’ description of the berserk, the Wotan army: “Those fierce men improve on their savage nature by enlisting the help of art and time: they blacken their shields, they dye their skin, and they choose the darkest nights for battle. The horror alone and the darkness which envelops that doleful army (feralis exercitus) spreads terror: there is no enemy who can withstand that strange and, so to speak, infernal aspect; because in each battle the eyes are the first to be vanquished” (Tacitus quoted by Benveniste 83). Let us dwell for a second in that last phrase, “the eyes are the first to be vanquished.”

The attempt to think about the mere possibility of a posthegemonic politics, which means first of all a politics not bound by constraint and obedience, a politics that takes its point of departure in the assumption that persuasion means submission and domination, has been linked to an existential practice of freedom from domination, which we call infrapolitics. Infrapolitics does not attempt persuasion to the extent that it does not attempt domination or calls for obedience. Indeed, it places itself at the limit of any political practice, in a dark area at the border of political logic.

Benveniste starts his dictionary entry by talking about oaks, a solid tree, the embodiment of firmness and reliability. In old Germanic the oak was connected with the idea of trust, and trust was above all the virtue of a band of warriors. Friendship and community were originally and essentially the friendship and community of the warriors in a given band. The Greek word laos means both “army” and “the people.” Which means that politics is always first of all a politics of friendship, where friendship cannot avoid the hierarchies that pervade it, and which are expressed in the obligations of submission and command. So what happens when an obscure group of people, a group of friends, proposes a way of thought that subtracts itself from submission and command, and that suspends war in that sense? What kind of weird politics of friendship is at stake in a group that denies the traditional understanding of politics as much as it denies the traditional understanding of friendship?

Infrapolitics (and posthegemony as its corollary) cannot constitute themselves as a region for allegiances against a common enemy, it must subtract itself from it, prefers not to engage in enmity as primary political deployment, it dwells otherwise. But this has two immediate effects. On the one hand, it preempts the deployment of any libidinal drive connected to group militancy (not the miles but the unherdable cat is the referent here), which means that it also preempts mimetic rivalry. These two, the mimetic drive and mimetic rivalry, are two archaic characteristics or dimensions of the band of brothers, and they are probably unrenounceable as such. On the other hand, upon offering itself as an exception, it seems to undermine the very constituting principle of community at every level (trust, obedience, submission, mimetic drive, mimetic rivalry). It generates the impossible phantom of an ever more obscure, more abstract, radically opaque countercommunity, which of course unleashes every instinct for danger and therefore every reason for rejection.

That is to say, the infrapolitical form, as a theoretical option, must deal with two antinomic, hence destructive problems (they are destructive to the extent that aporia, no exit, is destructive): it does not encourage any will for mimetic solidarity, and it cannot avoid the massive rejection of the rival (another warrior) who suspects an enemy all the more dangerous to the extent it dissembles its enemy position, an enemy without a name, an obscure and unidentifiable enemy to the extent it places itself outside the common light, the solar space. To that extent it appears to be a berserk enemy, a feral and infernal soldier of the dead and nocturnal Wotan: the feralis exercitus of the infrapolitical mofos; of those who have, and want, no exercitus.

As far as infrapolitics and posthegemony go, the eyes are the first to be vanquished, and nobody wants to look beyond. Perhaps nobody can, or they prefer not to. This is, needless to say, unjust.

De poder escogerme quiero por contemporáneos a Gerónimo y a Kafka. Me sobran las palabras de la historia, la estúpida mansedumbre de Penélope. (Miguel Morey, Deseo de ser piel roja [Barcelona: Anagrama, 1994] 54)

La cabeza empieza a ser ahora una ciudad que sólo mis pies conocen—ellos me conducen, y está bien. Ignoran las razones de la línea recta y la distancia más corta—y en cambio saben bien la virtud de todos los rodeos, todas las bondades del desencaminarse. Descarriado, aquí y allá, las cosas cambian: la ciudad es otra a cada paso y, sobre ella, los cielos siempre están abiertos. Lo sé. Sé que muy pronto seré un hombre libre—libre incluso de amenazas como las de los monstruos de la noche. Lo sé, igual que tras la muerte de la muchacha de blanco el vaquero sabía que nunca regresaría a casa—que no le quedaba ya sino la llamada de la pradera, y que era entre los pieles rojas donde tenía su última confianza de encontrar su tierra y su gente. Ahora lo sé—con esa clase de certidumbre. (Morey, Deseo 146)

Antes del fin

Deseo de ser piel roja es una obra publicada en 1994, y así presumiblemente tiene poco que ver con la pandemia que nos cerca. Pero el narrador, indecidiblemente figura del autor o criatura de ficción, aunque el texto se esfuerza por hacerle sentir al lector su tono autográfico, no deja de insistir en que su cabeza es una ciudad sitiada, una ciudad amenazada: “tu cabeza es siempre una ciudad en estado de sitio” (47). Además, dice: “Los tiempos que comenzaron entonces fueron tiempos de vigilarse uno mismo, de escucharse, de hacerse caso: cuando sientes que vas aprendiendo algo de lo más elemental, como que es prudente no hacer más de una cosa a la vez, y hacerla lentamente . . . –y que lo más importante ahora es ser prudente” (87). Para extraer una lectura apropiada al momento propongo prescindir de la estructuración edípica o postedípica del relato en sus nudos centrales (“las páginas que siguen no son, pues, una novela psicoanalítica,” se dice, quizás para poner en juego el mecanismo de denegación y mentir con la verdad [13]) y fijarme en esta nota solo en su parergon, en el marco, o en algunos aspectos del marco. Eso concierne a “la espera,” al “tiempo muerto de la espera” (15) del que todos habremos aprendido algo en estas semanas.

El narrador busca libertad, aunque sea la libertad amenazada del apache antes de su exterminio. Si el apache entiende “que la vida de la libertad no admite más que tiempo presente” (33) puede decirle al vaquero bueno “aléjate—los de tu raza se han condenado a habitar para siempre en una tierra que no existe, en algo como esa distancia que separa al rayo del trueno. Han escogido ese camino donde siempre es de noche” (36). El narrador busca, al tiempo esperanzada y desesperanzadamente, una “Fuga” (39), de la que sospecha: “como viviendo una realidad en la que no cabe soñar con que lo posible le abra algún día una brecha” (45).

Esa brecha en lo real es lo que se espera en la “ciudad en cuyas afueras sólo florece el alambre de espino” y donde “los últimos hombres rojos deben esconderse en las catacumbas para bailar la Danza del Presente” (49). Con respecto de ella “saber que se es alguien que huye [de la mirada fija de todos los hombres máquina (75)] ya es un modo de no estar tan perdido” (70).

Para evitar la pérdida, ¿qué se busca? La meditación, a través de todas las historias, es sobre el tiempo de la vida, con respecto del cual uno es siempre un superviviente hasta que deja de serlo. Por eso el narrador busca otro tiempo, un presente, así entendido: “Conoces hasta el fastidio ese pequeño desgarro sostenido que es comprender que nunca será el tuyo el acomodo propio de habitar una especie de instante interminable—la limpia inmediatez de quien está en el mundo como debe estar el agua dentro del agua. Que estás condenado a no poder vivirte sino en la revocación de lo vivido, en la representación de una vivencia que ya está ausente como tal cuando la identificas, cuando la interpretas y nombras—que pertenece al instante, al segundo, inmediatamente anterior” (163). Pero ese pequeño desgarro sostenido es cabalmente angustia originaria, generadora de todas las historias justo en el empeño de prescindir de toda historia, de fugarse, no del tiempo, sino del tiempo robado en el sentido. La brecha en lo real atiende al intento de destruir el sentido para encontrar en su ruina, imposiblemente, su misma redención. Por eso, del “sentido que late inminente en el intersticio abierto,” “algo te dice que sólo este intersticio te puede permitir escapar, cumplir con tu anhelo de hombre rojo por entrar en el presente” (199).

El momento de la más perfecta coincidencia entre la luz del rayo y el ruido del trueno es el momento de la aniquilación, pero el trecho que se extiende entre el rayo y el trueno es el tiempo terrible de una ausencia en el que se construye el sentido como compensación y consuelo. Ese es, en cada caso, el tiempo muerto de la espera, el tiempo ya carbonizado en el camino nocturno de los hombres-máquinas. No es el tiempo apache, excepto en el sentido de que ese es el tiempo destruido.

Es posible que la brecha en el tiempo muerto e improductivo que vivimos, en la espera, rescate la memoria improbable de un existir no entregado al “transcurrir curricular” (169), que es hoy la razón común de toda soledad singular. Esa sería una prudencia plausible, una fuga política.

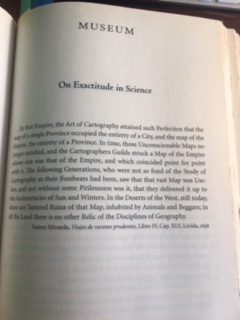

. . . In that Empire, the art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

Suárez Miranda, Viajes de varones prudentes, Libro IV, Cap. XLV, Lérida, 1658. (Jorge Luis Borges, “On Exactitude in Science”)

Tiqqun’s The Cybernetic Hypothesis, from 2001 but just published in English translation, starts with an epigraph from Jean-François Lyotard in reference to Borges’ text on maps and territories. Perhaps the key to it is its first sentence: “The great concentrator wants stable circuits, even cycles, predictable repetitions, untroubled accountability. It wants to eliminate every partial drive, it wants to immobilize the body” (Lyotard quoted by Tiqqun 10). To map a territory to the most exact extent is to replace it, in perhaps the same sense Antonio Gramsci dreamed of when he said the communist movement would not conquer the State but would perfect it by replacing it. The substitution, however, breeds a particular immobility: the map is after all the territory brought to a standstill, to a fixity that only time can ruin. Time, or the plague: the Cartographers Guild could not have foreseen the invisible irruption of the virus that reintroduces a now irretrievable gap between map and territory. Any dream of reproduction and control, of reproduction by means of and in view of control, is shattered. The gap, the virus, destroys the speculative project through a multiplicity of zones of opacity. And then what?

“Cybernetic [capitalism] asserts itself by a negation of everything that escapes regulation, of all the lines of escape that save existence in the interstices of the norm and its apparatuses, of all the behavioral fluctuations that ultimately would not follow from natural laws” (27). The “total modeling” (43) of the cybernetic hypothesis flounders. “Total transparency” (55) ends in a chaos of solitude. Surveillance and capture, after all, the twin apparatuses of cybernetic capitalism, are premised on the absolute equivalence of map and territory. The uncertainty the gap introduces throws a wrench into the workings of their will-to-power whose reconstruction is now, perhaps transitorily, in doubt.

Another epigraph, this time from Giorgio Cesarano: “The fictitious constantly pays a higher price for its strength when beyond its screen the possible real becomes visible. It’s only today, no doubt, that the domination of the fictitious has become totalitarian. But this is precisely its dialectical and ‘natural’ limit . . . in the bloody sinking of all the ‘suns of the future,’ there begins to dawn a possible future at last. Henceforth, in order to be, humans only need to separate themselves once and for all from every ‘concrete utopia’” (Cesarano quoted by Tiqqun 119). The separation is not simply willed: it occurs, dystopically and ineluctably. Its name is “panic” (122), a “disintegration of the crowd within the crowd” (123). “It’s the end of hope and of every concrete utopia that takes form as a bridge extended towards the fact of no longer expecting anything, of having nothing left to lose. And through a particular sensitivity to the possibilities of lived situations, to their possibilities of collapse, to the extreme fragility of their sequencing, it’s a way of reintroducing a serene relationship with the headlong rush of cybernetic capitalism. At the twilight of nihilism, it’s a matter of making fear just as extravagant as hope” (125).

The “invisible revolt” (160), as invisible as the viral irruption, proliferates secretly, inconspicuously, through the constitution of zones of opacity “in which to circulate and experiment freely without conducting the Empire’s information flows” (161). There are anonymous singularities that have broken and are breaking loose. They must now experiment. The thought experiment must go through what Jacques Derrida, in his Theory and Practice Seminar, called l’incontournable. Thought returns to its calling as an attempt to open to what is both inevitable and obscure, ineluctable and necessary but remote and forbidden. It cuts through Cesarano’s fictitious because it has forcefully been exiled from it. The radical denarrativization the virus wreaks into the very fabric of the illusion of the speculative dream, cybernetic capitalism, leaves us open to a silence we have perhaps never heard before, never experienced. That opaque silence is also the promise of a future.

Alberto Moreiras

Works Cited

Borges, Jorge Luis. “On Exactitude in Science.” In Collected Fictions. Andrew Hurley transl. New York: Penguin, 1998. 325.

Derrida, Jacques. Théorie et pratique. Cours de L’ENS-Ulm 1975-76. Paris: Galilée, 2017.

Tiqqun. The Cybernetic Hypothesis. Robert Hurley trans. Pasadena: Semiotext(e), 2020.

(This is the first posting. The idea is for some of us to read systematically the Gramscian oeuvre. Those in the reading group who so desire will post 500-word comments, just notes for discussion, with an aim to accurate understanding, and there might be discussion follow-ups in this space, although we mean to have the primary discussions through Zoom every three weeks or so. We begin with the Pre-Prison Writings, which, we understand, do not necessarily represent the mature Gramsci in every respect.)

The Hegelian ethical state, accomplished through the bourgeois revolution, is not enough. We must move towards the construction of an organic state, which only the Party, as the shadow government of the proletariat, can prepare. It is a matter of culture over economics: culture enables the proletariat to know itself, that is, to accomplish self-consciousness through the “disciplining of one’s inner self,” through the “mastery of one’s own personality,” through the “attainment of higher awareness” that will lead to understanding the place of the proletariat as universal class in history. That will naturally determine “our function, rights and duties” (9-10).

History is therefore “the supreme reason” (13). And history teaches us that the unleashing of productive forces, a “greater productive efficiency” that will eliminate all the “artificial factors that limit productivity” (15), will bring about communism. It is therefore a matter of “exploiting capital more profitably and using it more effectively” (16). Yes, towards equality and solidarity, love and compassion (90). This is the truth of history, and “to tell the truth, to reach the truth together is a revolutionary, communist act” (99). This will be “the final act, the final event, which subsumes them all, with no trace of privilege and exploitation remaining” (48).

Thinking is being, and being is history. There is an “identification of philosophy with history” (50). This is why Marxism is “the advent of intelligence into human history” (56), which is equal to “identifying [historical] necessity with [man’s] own ends” (56). This is the task of the Party. “Voluntarism” is the task of the Party, and it is “about the class becoming distinct and individuated, with a political life independent, disciplined, without deviations or hesitations” (57). Until it can, not conquer the State, but “replace it” (62).

The Party is all, but it is only the vanguard of the all. “Most people do not exist outside some organization, whether it calls itself the Church or the Party, and morality does not exist without some specific, spontaneous organ within which it is realized. The bourgeoisie is a moment of chaos not simply where production is concerned, but where the spirit is concerned” (72).

When Gramsci discusses the Italian liberal Constitution existing in 1919 he notes that Italians have been living under a state of exception for several years. The exception reveals the rule, he says, and the rule is the rule of domination by bourgeois interests as expressed by liberalism. The situation post-state of exception, in the wake of the Russian Revolution, might enable the unleashing of true history. “The proletariat is born out of a protest on the part of the historical process against anything which attempts to bog down or to strait-jacket the dynamism of social development” (88-89).

The Party will lead, by submitting to history and its unleashing, the people in order to create, through “ceaseless work of propaganda and persuasion,” an “all-encompassing and highly organized system” (99). Freedom is party discipline (26).

Me parece que hay muchos que están, respecto de Giorgio Agamben y sus posiciones sobre la política gubernamental generalizada en torno a la pandemia, en la posición de la muchacha griega que se reía de Tales de Mileto porque se cayó a un hoyo por mirar el cielo. Sí, todos somos, como Tales, un poco idiotas cuando llega el momento, pero quizá no convenga reírse tanto. Lo que quiero decir merecería y merece más trabajo que el que ahora tengo ocasión de dedicarle, pero quiero redactar esta nota como recordatorio futuro. Lo hago después de leer varios textos y entrevistas con Agamben, pero también después de haber leído el cuidadoso texto de Sergio Villalobos-Ruminott respecto a la polémica que esos textos y entrevistas inician (https://infrapolitica.com/2020/04/23/el-affaire-agamben/). Sobre todo lo hago porque, en esta última semana del curso, acabo de leer y discutir con mis estudiantes el par de capítulos que José Luis Villacañas le dedica a la Inquisición española en su libro Imperiofilia (Madrid, 2019). Remitiéndose a trabajos suyos anteriores, Villacañas expone que el “partido fernandino,” esto es, los partidarios de Fernando de Aragón, lograron estabilizar un poder monárquico cuya función política negativa más importante fue destruir el poder de las ciudades españolas y desmantelar su control fiscal para apropiarse de él, y que la Inquisición fue el instrumento idóneo para ello, puesto que los conversos eran sus élites políticas y en muchos casos económicas. Y entonces dice Villacañas (perdón por la larga cita, pero creo que está ampliamente justificada): “Dada la práctica posible de la delación, el miedo a ser investigado por cualquier vecino rompió todo vínculo comunitario real. Ese miedo particular a un tribunal de Estado cuyos agentes eran los mismos vecinos—los famosos familiares—es el tipo de sentimiento que no puede fundar comunidad. Al contrario, el Tribunal solo podía funcionar quebrando vínculos comunitarios previos y, cuanto más cercanos fueran, más oportunidades daban para fundamentar la denuncia. La desconfianza se impuso por doquier. De este modo, el Tribunal solo producía cristianos nuevos discriminados y señalados, y dejaba el resto bajo el manto de una cristiandad vieja que siempre era provisional y que seguiría siéndolo en la medida en que no fuera investigada. Todos eran en el fondo todavía no cristianos nuevos. Así se extremó la fidelidad a un rito externo que nunca en el fondo protegía ante la realidad ancestral de la sangre, siempre discutible, pues dependía de lo lejos que se llevase la investigación. Podemos llamar a esta que forjó la Inquisición una comunidad negativa, pues solo identifica al que sale fuera de ella. Los demás se mantienen implícitos e inseguros. Lo que sale a la luz y se destaca es siempre su fractura y sus consecuencias: confiscación, mancha perenne, ciudadanía de segunda, discriminación y el miedo que reverbera en todos los demás, que se saben investigables, dado el largo proceso de enlaces interraciales matrimoniales previos. Aunque todos se reúnan en la iglesia, o en el auto de fe, nadie se sabe completamente libre de estar en el otro lado. Todos se aferrarán con tanta más fuerza al rito público cuanto más teman ser mirados por el Tribunal y separados de aquel. Lo que unía en todos los casos no era la confianza recíproca, sino el no ser mirado” (Villacañas, Imperiofilia, 161).

La “comunidad negativa” está marcada por una pertenencia precaria y absolutamente interrumpible, y por lo tanto absolutamente deseable, y a la vez está constituida, paradójicamente, por aquellos que salen de ella y entran en el afuera inquisitorial, que viene a ser también, por lo mismo, la interioridad más íntima en todos los casos. Esta comunidad contradictoria es como aquella figura que, por ser una figura aporética, sin afuera y sin adentro, era la mejor representación de ciertas fuerzas del inconsciente que le gustaba invocar a Lacan: invivible, pero condición de vida. El viejo historiador de Pennsylvania Henry Charles Lea decía que, bajo la Inquisición, nadie podía ya existir excepto en la sombra del terror. El país entero quedó sumido en la sombra del terror, que no por potencial era menos terror en la medida en que el terror siempre es potencial y nunca encuentra estásis. En cuanto a Agamben, podemos pensar que su reducción de la posición del humano en el presente a homo sacer o vida desnuda es excesiva, en tanto no somos todavía sujetos de vida desnuda, igual que un converso toledano no caía bajo la Inquisición hasta que caía bajo la Inquisición. Pero lo que cabalmente propone Agamben, como Villacañas para la comunidad de los cristianos viejos que “todavía no” habían perdido su calificación, es que la vida desnuda es el sentido tendencial o potencial de la vida en nuestro horizonte civilizatorio. Desde ese punto de vista no sería tan descabellado proponer que nuestras comunidades son igualmente comunidades negativas. Si es posible que la reducción de la vida de cada cual a vida desnuda sea el horizonte biopolítico fundamental de nuestro tiempo, y si es posible por lo tanto, como propone Agamben, que en cada uno de nosotros haya siempre un homo sacer latente, listo para ser ejecutado sin asesinato ni sacrificio, listo para pasar a disposición de la autoridad pertinente, política o médica o laboral, no debería sorprender que el elemento político dominante en nuestro mundo sea negativo y contracomunitario. Igual que la Inquisición en España produjo una comunidad social negativa y aterrada, también las tendencias civilizatorias descritas por Agamben la producen y la vienen produciendo. Eso es lo que él señala, y quizá lo que produce mayor irritación en sus palabras, en estos momentos de la pandemia. Su preocupación—quizá monotemática y en ese sentido sujeta a la risa de la muchacha de Mileto–es que las actitudes gubernamentales generales son parte de esa lógica y no una excepción a esa lógica. No es tan fácil discutirlo, pues no será fácil acertar a formular una solución al problema ni improvisar un cambio civilizatorio inmediato.

La estructura inquisitorial causó un colapso de toda posibilidad política en España durante siglos–había un poder dentro del Estado, un poder intocable, que era superior al Estado mismo, y con respecto de él no había emancipación predecible. De la misma forma la estructura homo sacer tiene esa potencialidad de producir colapso político y comunidad negativa: si somos solo en la medida en que no somos vida desnuda, y así vivimos en el resto que hay entre nosotros y nuestro abismo como vida desnuda, en el que nunca querríamos caer, es fácil que nuestras ideas de comunidad no sean más que la deseable impugnación imaginaria de tal estructura existencial. No es solo comunidad negativa la que se organiza condicionada por la potencialidad reductiva del homo sacer biopolítico, sino que también las soluciones o reacciones comunitarias solo a medias pensadas y solo a medias concebidas acaban siendo igualmente contracomunitarias o dando origen a comunidades perversas (nacionalismos, sectas, ideologización radical). Esto es a mi juicio importante y muy valioso y hay que agradecérselo al pensamiento de Agamben.

La otra cuestión que a mí me preocupa cuando le leo es que su solución a todo ello, en cuanto solución política, no me parece todavía persuasiva. A mi juicio se hace necesario someter a Agamben a un pequeño ajuste de los que a él le gustan (recuerden que admira mucho el “pequeño ajuste” de Benjamin con alguna fábula de Scholem o de Kafka o de ambos). Y ese ajuste es que, si somos solo en la medida en que no somos vida desnuda, ese ser debe atenerse, para ser propiamente, no a una inversión de la comunidad negativa en positividad imposible o gloriosa, no al juego de la inversión contracomunitaria hacia la animalidad del fin de la historia, sino más bien al logro de una exterioridad radical, ni inquisitorial ni biopolítica, con respecto del mundo socio-político contemporáneo, y tanto más radicalmente cuanto más totalitario sea este último. Y esa exterioridad es ejercicio infrapolítico, y acaba constituyéndose, por poco que se piense, como condición de toda política que no sea meramente la inversión de lo que hay, y así, por ende, todavía parte de lo mismo. No hay emancipación por ese lado. No es, por lo tanto, diría yo, ni la soberanía ni la violencia ni el poder lo que más preocupa a Agamben (o si lo es lo es solo en la medida en que trata de hurtarse a todo ello), sino cabalmente todo lo contrario.